The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks M.C. C.D.

A Canadian Hero

|

|

|

|

I soon realized that it would be most difficult to escape from the main camp. The Air Force Compound was isolated from the other compounds. The entire camp was guarded by searchlight towers, machine gun nests, warning wires, patrols and police dogs. Airmen had less chance to escape than soldiers. This was because airmen couldn't be sent out on working parties and the boys in the army could. The majority of the lower rank POWs held in StaLag VIII B were not in the main camp but in smaller working camps known as Arbeitskommandos. (Arbeitslager is a German language word which means Labor camp or work detachment.) When I was there approximately 65 subsidiary Arbeitskommandos were set up to house lower ranks that were working in the coal mines, quarries, factories and on the railroads.(In later years the number of Arbeitskommandos would grow considerably.) The Geneva Convention that the Germans were signatories to, set out that enlisted ranks were required to perform whatever labour they were asked and able to do, so long as it was not dangerous and did not support the German war effort. This was of great benefit to the captors as it freed up able-bodied Germans to fight at the front. The Arbeitskommando units were significantly less well guarded than the main camp, the degree of security depended upon the amount of trust earned by the POWs and their nationality. For example, French POWs were considered such low-risk that they were allowed to go shopping on their own in towns, trusted to come back on their own accord. Russians, conversely, were always heavily guarded. Commonwealth troops were somewhere in the middle. Escaping the guards was the not necessarily the hardest part of any potential escape attempt, however not when the closest neutral country or front line was over 500 miles away. The vast majority of escapees were quickly captured within a day or two and received a minimum of a month in solitary as punishment for their escape attempt. |

|

Some images follow which provide a snapshot of prisoner life within Stalag VIII B.

(Editor's Note: See also the PHOTOS posted at the

web site Lambsdorf Remembered .)

|

|

Note in the above image at the bottom right the "tin can chimney" exiting the prisoner barracks!

Senior non–commissioned officers (sergeants and above) were required to work only in a supervisory role. Commissioned officers were not required to work, although they could volunteer. The Germans often viewed this with some suspicion and the oficer was 'monitored'.

The answer then, to provide an opportunity to escape, was to become a soldier! And so I started to ask around discreetly until I found a soldier who would be willing to exchange identity with me. It had to be someone roughly the same height and size as me with the same color hair and eyes, but the resemblance fortunately, did not have to be too close.

There were no real escape committees in those early days; you planned your own breaks.

The Escape Committee in those early days was more like a traffic cop ensuring that any escapes did not overlap, especially with a well thought out plan. My plan was to avoid any conflict and make it a two step process by first exchanging identies with an enlisted soldier, get assigned to a work party, and then escape - preferrably with someone who knew the area.

A British Pilot with the first name Lawrence was rumored to be on the Escape Committee and, fortunately, he ate at the same dinner table as myself. I broached my interest in escape to Lawrence and he indicated he might be able to help me indirectly. (Membership in the Escape Committee was strictly secret.) In short order, another dinner table companion, RCAF photographer Ken "Tex" Hyde made contact and listened to my plan and gave the Committee's blessing.

Many of the early prisoners had their identity card photos taken when they were thin and haggard after prolonged forced marches and the guards could not identify them too well this way.

It was in a crowd of prisoners watching a soccer game that I finally found a man willing to make the switch.

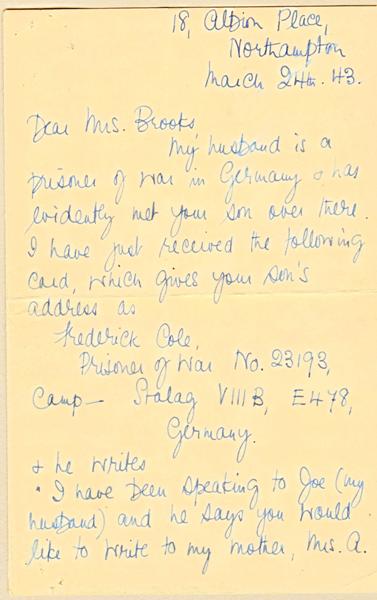

He was Private Frederick Selwyn Cole, POW #23193, a soldier (Serial Number 2815) in the N.Z.E.F.'s 18 Battalion New Zealand Infantry.

Before enlistment, Fred had been a barman from Whangarei, New Zealand. (Whangarei is located just north west of Aukland - where Fred was born - on New Zealand's north island.)

The willing Kiwi had just arrived back in Lamsdorf from a work party and he was happy enough to exchange the hard grind for the leisurely life of a flight sergeant in the Air Force Compound.

Cole was about 6 years older than me (b. Dec 1915), had a tatto, been wounded May 1941 in the fall of Crete and a P.O.W. since summer of 1941. On the plus side he had blue eyes, dark hair and was about 5ft 10in. in height. Under normal circumstances I would never be confused with Frederick Cole. But without proper identity cards and everone looking a bit thin and haggard most anything was believable in a P.O.W. camp!

Cole had been part of the Allied Lustre Force rescue effort of Greece and Crete and had been captured at Crete as a consequence of German General Kurt Student's successful parachutists invasion of the Mediterranean island May 1941 (Not only the first battle where German paratroops (Fallschirmjäger) were used on a massive scale, but also the first mainly airborne invasion in military history).

Switching identities was as easy as changing suits. That was all we did. A few days after our first meeting we both reported on sick parade. Once inside the bustling camp hospital we dodged into a washroom. I peeled off my Air Force blues and he took off his khaki battledress. Five minutes later I was marching back to the army compounds as a New Zealand private.

I was not aware of the flurry of correspondence to my parents that subsequently my exchange of identity with Private Cole.

The R.C.A.F. had a much more efficient sytem to record identity switches. The index cards below illustrate their methodology.

|

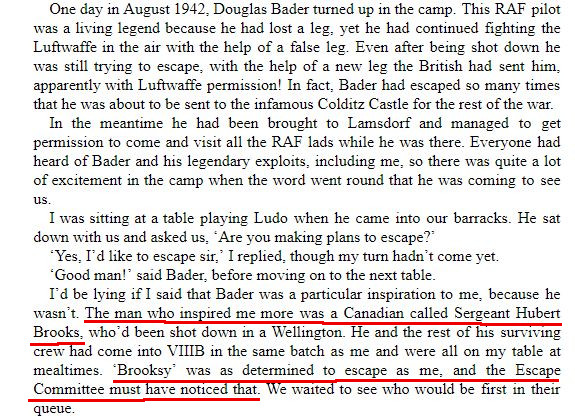

The book Down But Not Out, The Incredible Story of Second World War Airman Maurice 'Moggy' Mayne by RAF air gunner and Stalag VIII-B prisoner (dinner table mate to Hubert Brooks) Sgt. Maurice Mayne with Mark Ryan; sheds interesting colour on Hubert Brooks' escape plans (Chapter 9).

And further in chapter 10.....

|

It was odd to think that from now on a comparative stranger, one Fred Cole, would be living the life of Hubert Brooks, opening Red Cross parcels from Montreal and getting letters from my family.

But, the important thing was to escape and I was on my way!

| PREVIOUS PAGE | GO TO TOP OF PAGE FOR INTER- and INTRA- CHAPTER NAVIGATION MENUS |

NEXT PAGE |

The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks M.C. C.D.