The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks M.C. C.D.

A Canadian Hero

|

|

|

I reported to MRES Headquarters in London on 7–Nov–1945. We had a few days of general introduction and then I was given a 2–week leave pass as the next course was not set to start until Monday 19–November. Training lasted approximately 3 weeks.

MRES sections were to be formed from the Arctic Circle (Scandinavia), France, Holland, Germany, the Mediterranean / Middle East to the jungles of Burma and the Far East.

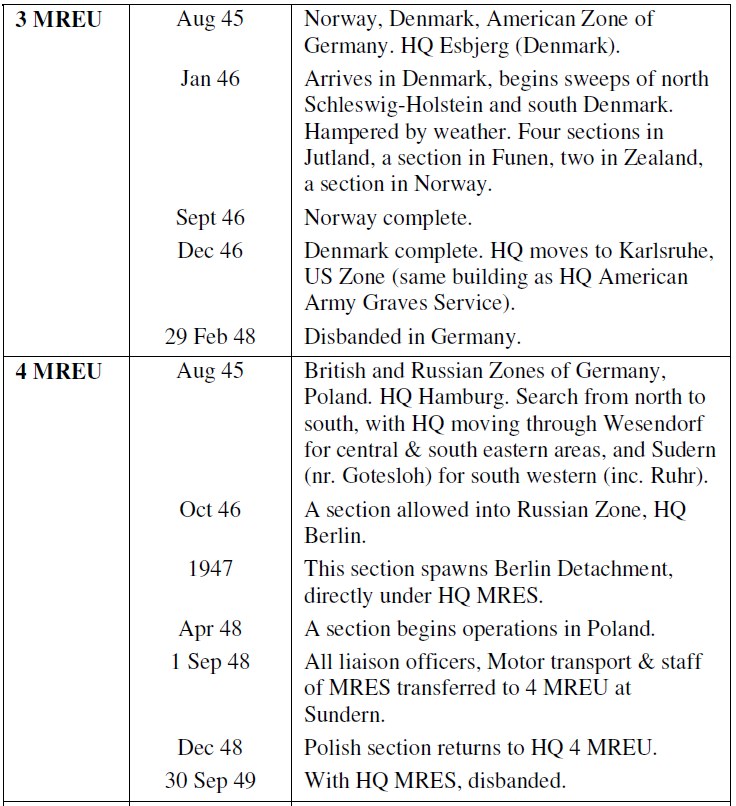

Eventually there ended up being 5 Missing Research and Enquiry Units (MREU):

|

|

|

The first MREU (No. 1) was established in Paris in January 1945 and initially consisted of 5 Search Officers. In April 1945 a second section (No. 2) was established in Brussels to operate in the Low Countries. In the coming months the organization quickly expanded and the other units were established.

The principle underlying the location of the units was to begin in the outer countries of Europe and gradually work inwards, with Germany and Central Europe as the final target.

Each of the 5 Units would be self–contained for operational and administrative purposes all reporting into a MRES Headquarters with a Group Captain commanding. Nominally each unit had a complement of 40 Search Officers who were divided into eight sections of five – a section having a Squadron Leader in charge of four Flight Lieutenants.

(No 4 Unit was the last survivor of the 5 MREUs. On 30th September 1949 this unit and the Headquarters of the MRES were disbanded, leaving behind the RAF Graves Service to continue the work of Missing Research and Graves Registration. Later re-named as the Commonwealth War Graves Commision or CWGC.)

I was to be in No. 3 MREU.

While at my training in London (on 1–December–1945) I was promoted to Flight Lieutenant – a rank commiserate with the job I was about to undertake as a Search Officer.

The magnitude of the 42,000 airmen lost or unaccounted for during World War II was staggering, and it seemed initially an insurmountable task with the size of team established.

We were a mixed crew who had volunteered for MRES. After six years of war, all military personnel had good reasons to simply go home so our volunteerism was very much appreciated. We were made up of men and women who had very little qualification for the massive scale detective work in front of us beyond our own experiences of the dangers, horror and lost friends; and what universally seemed as the sense of duty in seeking answers to the fate of lost comrades–in–arms. Each case solved carried a physical and a mental cost to the Search Officer. Every case solved laid a ghost to rest for a family back home.

One can obviously imagine and relate to the desperate need for any information concerning the fate of airmen

categorized as "missing presumed dead" by parents and relatives back home. Often times this led to desperate measures.

In 1948 an article in a British Sunday newspaper ( The People 28 November 1948) related the story of the father of a Canadian flight

sergeant reported missing on a wartime mission who had come over to England to pursue his own enquiries. One day at London�s Kings Cross

station he thought he came face to face with his son. By the time the father had recovered his composure the man had gone. For days afterwards

this father frequented the station hoping he would encounter the man again – but to no avail.

Sadly some parents could not bring themselves to believe their son was dead in spite of assurances from the Missing Research & Enquiry Service that there was absolutely no evidence to the contrary.

We were told that we as airmen had been singled out for the MRES job because:

By our training we were typically:"obstinate, pedantic, had an eye for detail, were familiar with aircraft, airmen and the associated paraphernalia and we were intelligent!"

Our Air Force knowledge would assist us identifying and dating equipment and clothing.

Our war experience would have hardened us to the task at hand.

Many of us were former PoWs so we had some first hand experience with air crash sites. (A number of the early MRES officers were recruited from the English PoW resettlement centers of Church Fenton, West Maling and Wittering.)

Since most of us were volunteers – a high degree of commitment was expected.

Clearly initiative and dogged perseverance was needed for this job. It was stressed that the example summary reports we were shown from existing solved cases did not sufficiently reveal the great amount of study and initiative expended. A great deal of the work effort would be of an unspectacular nature, involving hours of hard application but with little to show for it. Some of the problems however would lead to very interesting and gartifying solutions.

It was thought that the requirements for a Search Officer required an officer at a rank of Flight Lieutenant or higher as it involved knowledge and experience, and, for the majority of cases, calls for unorthodox treatment and exceptional tact; from a point of view of contact with the public, and the representation of this important side of the work, the higher the rank would confer undoubted advantages.

It was made clear that this would be a gruesome task. In fact this would be one of the most daunting tasks undertaken by the RAF/ Commonwealth forces.

One was sure to face difficulties in terrain and climate, not knowing if the local people would be friendly or hostile. It was suggested that some civilian populations in Europe (especially Germany) might have mixed responses to the MRES in reviewing their actions in the treatment of the remains of lost aircrew.

One would be working against the odds to find, identify and give decent burials to the many thousands of airmen lost on operations.

It was simply unacceptable that any airmen heroes would remain in an unmarked mass grave in a nameless corner of a foreign field or left exposed at a crash site.

In an era before the modern terminology of "closure", this was exactly what the MRES attempted to bring to the families of those lost.

Page 34 of MRES Report AIR 55/65 Ref: 6.1 summarized this Serach Officer selection and training philosophy:

Some of the aspects covered in our training session included:

We reviewed some of the technical aspects of seeking out the wreck sites and recovering the bodies and then the commemorative nature of honoring the deceased that would follow.

We would each be given detailed maps and what intelligence and police reports that were available for

our assigned areas as per downed aircraft.

Each missing aircraft had been logged by the Air Ministry, and a file started. Identifying marks and serial numbers of the

plane, of the engines, of any of the major on–board components were recorded along with any operational details of the

circumstances of the loss, and to this was added information gleaned from survivors, intelligence sources and German authorities

themselves.

As an example, information from the German Totenliste ie "Death List" would be provided. However we were

cautioned that the Totenliste list was often inaccurate – but at least it was a start.

We were to use all of these existing reports as jumping off points and use our initiative on–the–ground to close

existing case files and establish new ones.

Working to a Casualty Office brief was not the sole task of the Search Officer. It

was known that a significant amount of information was scattered all over the Continent awaiting collection. To collect this

information, we were to conduct "area sweeps".

In time the reports generated from these "area sweeps", or so-called "X reports" as they became

known, rivaled in importance the reports from the casualty section.

We would be supported by our regional HQ in matters such as funding and organization and co–ordination of ground, sea or air transport, hotels and local translators. However from time–to–time we might have to arrange ourselves. At this stage I could not have anticipated how much a problem transport (ground, sea and air) would become and how much time we as Search Officers would spend dealing with it.

We were instructed on likely candidates for interrogation in the local population and authorities. Potential witnesses and the local authorities should be sought out, including mayors, clergymen, grave diggers, police, medical staff, scrap dealers and any one else who may have been involved in dealing with a crash and its crew. Children who may have witnessed a crash were perhaps surprisingly excellent witnesses.

Typically we would be responsible for arranging any local assistance needed in recovery (such as mountaineering assistance), and organize respectful burial services.

We reviewed the list of standard supplies such as rubber boots, gloves and disinfectant etc that we would be issued and the importance of there use.

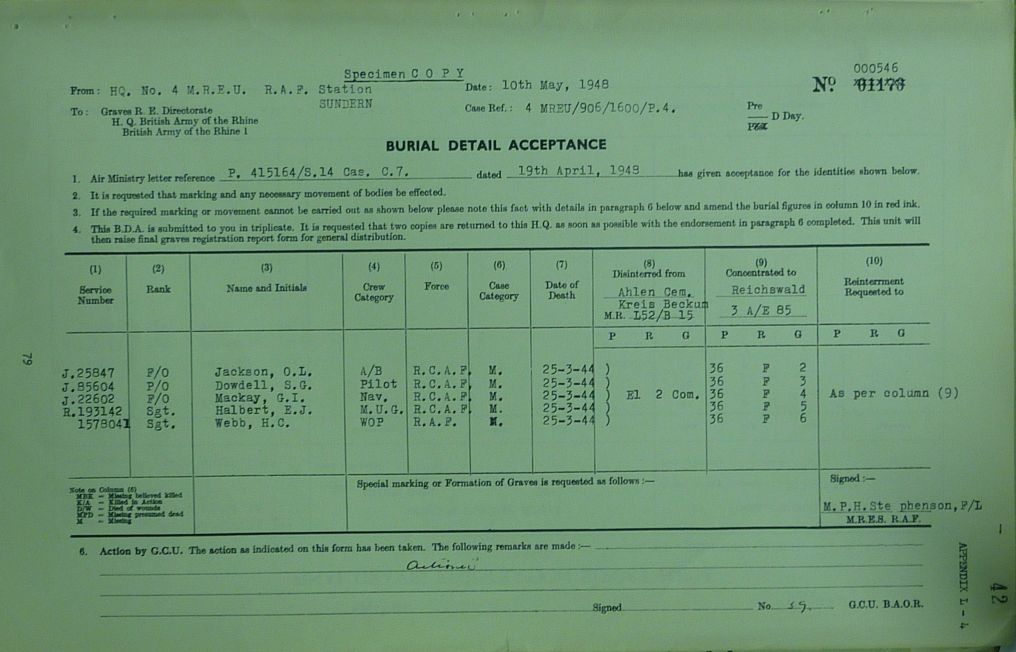

The different roles of the Allied Grave Registration Units (GRU) and the MRES were reviewed.

Typically recovered aircrew would be wrapped in Service blankets and handed over to the Army Graves Service for burial.

However in remote areas, Search Officers may have to transport bodies to local village cemeteries.

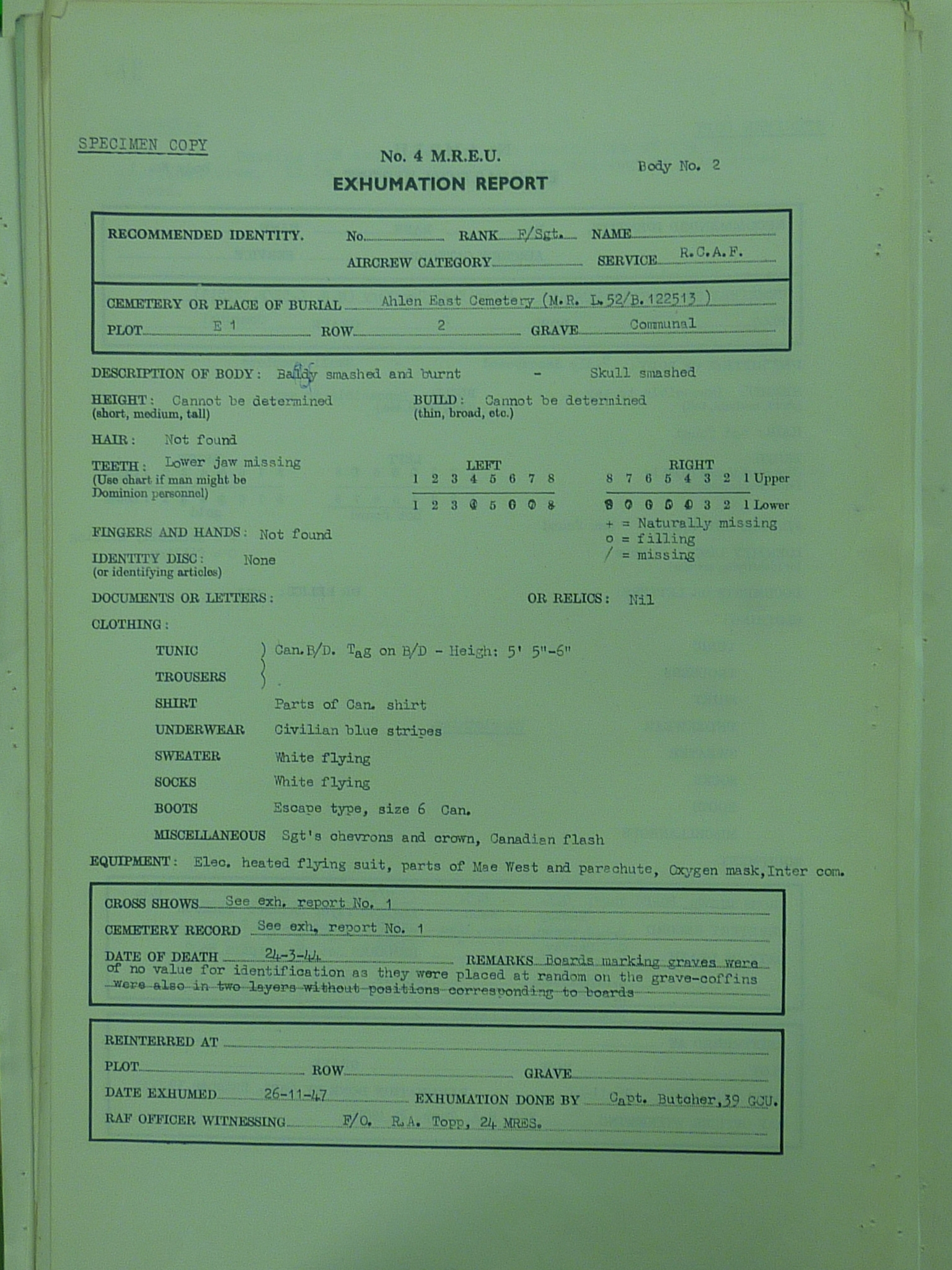

Normally, only the Graves Registration Units were allowed to exhume buried bodies, often using either German prisoners or local labor. The MRES could watch, and then conduct the examination, but were not allowed to physically open the graves themselves.

Once a grave was opened, if the bodies were in coffins they would be raised to the surface for examination.

If the bodies were not in coffins, then the Search Officer was to lower himself into the grave to study the remains in situ.

Once the body was exposed the MRES had a standard form to fill in, with a chart to show which body parts were retrieved.

Every little clue needed to be examined and recorded carefully.

The type of soil would be noted. This could be cross–referenced with the level of decay to establish a rough date of death.

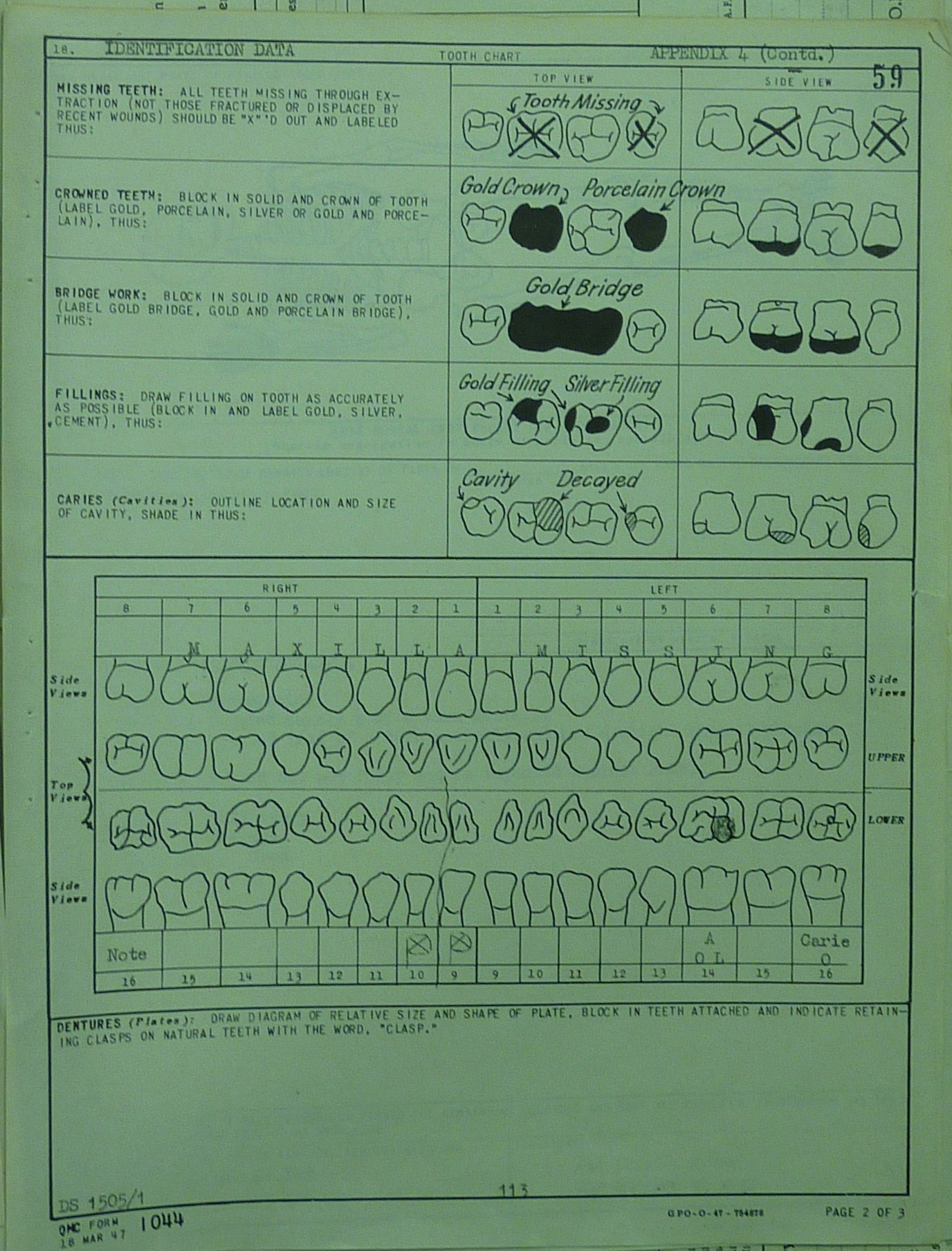

A basic physical description of the body was taken and a dental chart filled in.

Details of the uniform and equipment were carefully noted, as these would at least point to the nationality, rank and trade of the airman, based on the type and quality of the material and the insignia.

Personal equipment might bear the name of the wearer or at the very least a serial number that could at least be traced to the man issued with it.

Laundry labels or other potentially important clues were taken for later analysis and cross–reference as were personal effects (such as pipes, type of cigarettes etc)

One final act followed every exhumation. Standing Orders were quite clear that the first and last thing that a search officer should do on approaching or leaving a grave was to salute it.

We were instructed as to the importance of constant communication and the role of our HQ in assisting with the analysis and understanding of the information found in the field.

We were told that each of our assignments would be unique in some aspect or another, and that we were expected as search officers to take the initiative. Our work schedules would be coordinated with the local, regional HQ but would be largely ours in the making.

Finally, before being assigned our own investigation area, we would initially be teamed up with an existing unit in the field to see first hand a typical operations methodology.

Although it was emphasized that each case would be different, we went over some example cases illustrating some innovative and unusual methods of solution. A few of these cases with a Canadian slant are summarized below and illustrate a bit of the "detective nature" of this work(these cases are also documented in AIR 2/ 6330 Ref: 6.4 ).

A novel method of solving a problem was to enlist the aid of the press. The only clue in this case was a small locket case containing a photograph of an attractive girl as well as a second photograph apparently of the same girl, but in a nursing uniform, and a card on which was written an affectionate message to "Bob" from "Barb".

The case, with its contents was sent to the Air Ministry by Reay Headquarters, 2nd T.A.F. who had handed in a Frenchmen who stated it had been picked up "near a crashed aircraft". No information was available as to the type of aircraft or the date of the crash. The report however added that the pilot was buried as an "unknown" at Argenteuil (Seine et Oise). From this it was concluded, erroneously as it happened, that the aircraft was probably a fighter.

It was decided to invoke the power of the Press and the London morning papers carried a splash of the photograph, the signature of "Barb". A short story inviting identification was written.

The response was extraordinary; telephone calls, telegrams and letters poured in! Barbara was recognized from Land�s end to John O�Groats, and many points between! She was a W.A.A.F., a W.R.E.N., a dentist, a nurse (5 writers recognized her as a nurse and in view of the second photograph that had not been released these were immediately followed up). Barbara was also a very bad girl, at present in a Romand Home, and the wife of a baronet – this last suggestion was anonymous. Two letters, apparently from lunatics, had a certain entertainment value, but did not add to the sum of our knowledge. One contained complimentary references to Lord Dawson of Penn, and stated the writer had hurt his head, but was better now.

One writer enclosed a photograph of a girl he did not know, but which he stated "had fallen out of a library book at Hammersmith." Another writer enclosed the picture of a lady, who was in native attire, was attractive but was not Barbara.

Among this collection, however, there were three letters from members of the R.C.A.F., who identified Barbara as Miss Barbara Johnston, a nurse of Windsor Ontario, the fiancé of Flight Sergeant Robert (Bob)Whitley R.C.A.F..

Casualty Branch records showed that Flight Sergeant Whitley was an air gunner of a Wellington which failed to return from an attack on the Gnome–Rhone works at Gennevilliers, a north western suburb of Paris, on the night of 29/30th May 1942. The only information of the fate of this crew had proved misleading. According to the I.R.C.C. and a Totenliste the body of the Observor, Flight Sergeant Crawford, had been washed ashore or recovered from the sea on the 5th of June 1942, near Les Mareaux. German records stated that he had been buried there on the same day. No place of this name could be found, but MRES had been asked to investigate the possibility of Les Mureaux, on the River Seine, as it appeared likely that the body had been washed ashore on the river bank and not on the seashore as originally supposed. This line of enquiry was already being followed independently of the Barbara case.

R.C.A.F. HQ Ottawa was asked to obtain confirmation from Miss Johnston that she had in fact given the photograph and message to Flight Sergeant Whitley. Confirmation was received and the pocket locket case and contents were sent to her.

MRES followed up on these clues to the burial places of Flight Sergeant Whitley at Argentouil and Flight Sergeant Crawford at Les Mureaux.

It was known that Stirling BK 717, with a crew of seven, had crashed on 3rd July 1943, that one member of the crew had been killed and buried in North Cemetery, Flushing.

MRES had the grave numbers of four identified members of this crew, vis: 173,174,177,178; but grave 175 was given an unknown and grave no 176 was stated to contain the remains of Sergeant Plishka, R.C.A.F. 60893.

Sergeant Plishka was not a member of this crew. According to R.C.A.F. records a Sergeant of this name and number had been appointed to a commission and was presumed to have lost his life (probably in the sea) some four months later. Moreover his aircraft had not been operating near Flushing.

An enquiry to No 5 Section (Holland) revealed that "Sergeant Plishka" had been identified by the name and number on a tunic worn by a dead man. As it was impossible for the body to be Sergeant Phishka�s, it followed that the airman must have been wearing a garment returned to store when Plishka was commissioned. The wearer therefore must have been a sergeant.

The two members of the crew unaccounted for were Sergeant F.D. Field and Flying Officer J. K. Paterson. Paterson would not have been wearing garments issued to airmen. Therefore Sergeant Field must be the occupant of the "Plishka" grave, ie No. 176, and the remaining grave (No. 175) must be Flying Officer Paterson�s. Thus the whole crew was now accounted for and the relatives were informed accordingly.

At dawn on 14th October 1944, Halifax MZ 674 of 425 (R.C.A.F.) Squadron, with a crew of eight Canadians, took off for Duisburg. It crashed at Bracht, about 13 miles north–west of Munchen–Gladbach. Four of the crew were taken prisoner. Two were buried by the Germans in the cemetery at Bracht. Nothing was known about the remaining two.

When Search Officers began to investigate, they verified that the two crew members reported killed were buried in the cemetery at Bracht; and exhumation confirmed this. It was believed that the remaining two were still in the wreckage, and a salvage operation was undertaken.

The remains of the two bodies were found. There were manifestly the two bodies which had been sought, but the only clue to individual identity was the finding of an old pipe, well seasoned and repaired in two places. This would confirm the owner as a confirmed pipe smoker.

MRES asked R.C.A.F. HQ in Ottawa to contact the next of kin concerned. A signal came back to say that one of the two was a non–smoker and the other was a confirmed pipe–smoker; moreover he had written home saying that his pipe was broken and asking for a new one, which was on its way when he was reported missing. Thus one body was identified positively and the other by elimination.

All four dead members of the crew are now in individual graves in the British Military Cemetery, Reichswald Forest.

In March 1949 the body of a Canadian sergeant air gunner was found on the shore of Dunkirk. The discovery was published in the British Press which repeated an erroneous statement that the body was that of a 1940 casualty. A Search Officer was sent to investigate, and collect the body for burial. His view was that the body was a beach burial that had become unearthed by the force of the waves. It was taken for final internment to Pihem–les Guines Cemetery, Pas de Calais.

The report of this body gave the height as approximately 5’6” to 5’7”; slight build, hair on legs brown and in large quantities, hand missing and the bones badly smashed and broken. A hand–knitted white or khaki pullover, with label marked seize 36 was found. On one finger was a silver signet ring with the Prince of Wales Crest and initials "P.W. H.S."; on the inside was the inscription "Sterling Birks".

On receipt of the report, R.C.A.F. HQ Ottawa contacted Henry Birks & Sons, manufacturing jewelers. They stated that they made a ring as described for the Prince of Wales High School, Vancouver BC. The ring was manufactured not for the school itself, but for the sale to graduates in Birks Retail Store at Vancouver. No record of purchases was kept. This information established that the unknown air gunner was a graduate of Prince of Wales High School Vancouver.

An intensive and detailed investigation which involved interviewing personnel and teachers of the Prince of Wales High School who had been on the staff since 1935 revealed that approximately twelve graduates of the school had been reported missing in the R.C.A.F.. Names were secured and all but three were accounted for. The next of kin of these three were all interviewed. The father of the first stated that he had no knowledge that his son had possessed such a ring. The father of the second said that his son would wear a larger undershirt than size 36 and definitely established that his son did not possess a Prince of Wales ring.

The third candidate for consideration was Sergeant (Pilot Officer) J.M. de Nacedin, air gunner of Halifax NR 143, 434 (RCAF) Squadron, reported missing on the night of 5th / 6th December 1944. His father stated that his son�s height was 5ft 6in and his weight was 135lbs, and that he had large quantities of brown hair on his legs. He owned a khaki hand–knitted sweater and had taken it with him to the UK. As he was a man of slight build, it was reasonable to assume that he wore a size 36. The father also produced a photograph of his son taken while on operations and it showed a ring on one finger which could have been a Prince of Wales High School ring. All of the clues seemed to fit.

The Air Historical Branch of Air Ministry confirmed that Halifax NR143 had been routed to pass over Reading, England and cross the Channel near the south end of England. This routing would not be inconsistent with the place of discovery of the body.

In view of the circumstantial nature of the evidence, the father was interviewed in Canada once more. He was satisfied that this body was that of his son and asked for a grave to be registered in his name.

| PREVIOUS PAGE | GO TO TOP OF PAGE FOR INTER- and INTRA- CHAPTER NAVIGATION MENUS |

NEXT PAGE |

The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks M.C. C.D.