The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks M.C. C.D.

A Canadian Hero

|

|

|

|

|

| |

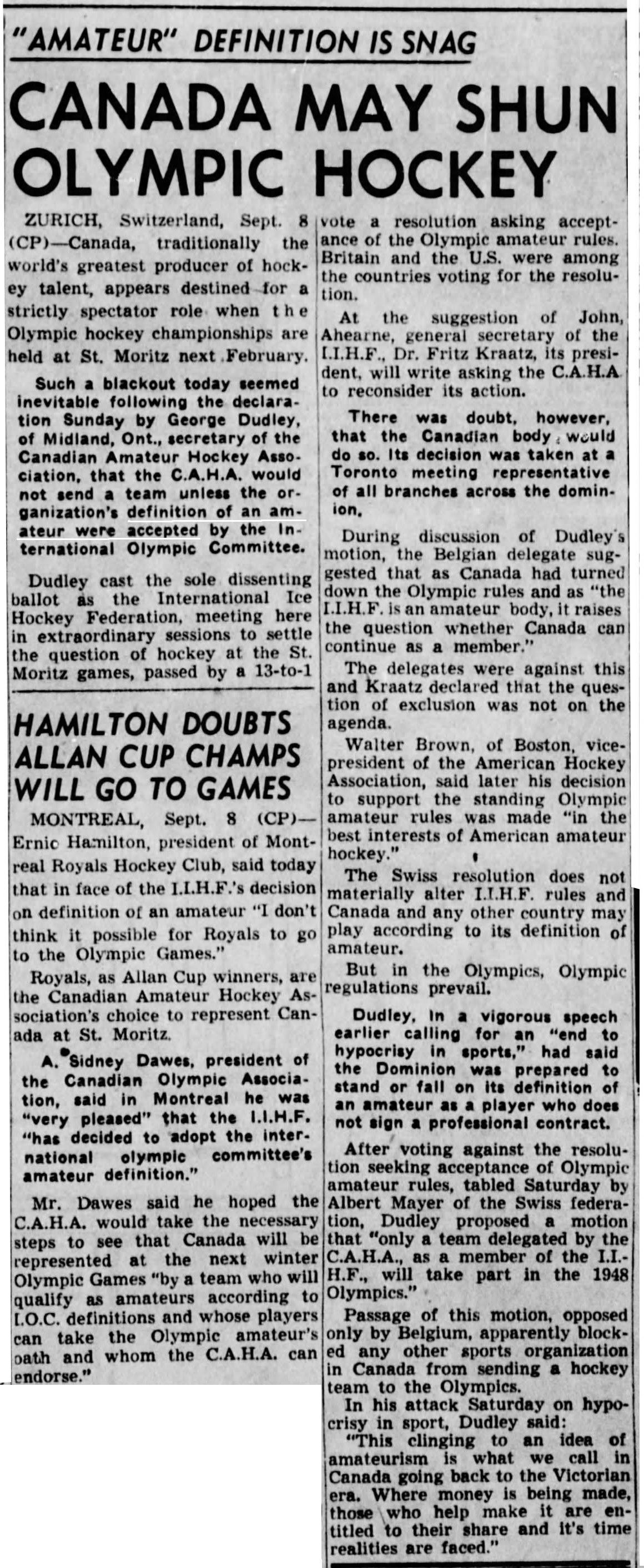

In late 1947, the International Olympic Committee instituted strict guidelines and thus revised the rules on what would be considered amateur status for Olympic competition. As the American team would eventually discover, these more stringent guidelines for the definition of amateur players were tough to get around. This blurry line between who was an amateur and who was a professional player would plague the Olympic hockey movement for the next half–century.

Canada was the only nation which opposed the decision. Canada wanted the definition of an amateur as someone

who had not signed a professional contract. The CAHA complained that even players in senior

leagues across the land probably did not qualify under the tough new rules imposed by the IOC. It would seem that under the IOC rules

only the wealthy would be able to afford to play and there certainly didn't seem like any reason why the Olympics should be restricted to the privileged few.

The Allan Cup champion Montreal Royals, which included future Hall of Famer Doug Harvey, publically announced that they could not

represent Canada at the Olympics. This announcement was devastating. Previous Canadian Olympic team entries were Allan Cup, or senior league

champions. These were teams that had played together certainly for months, if not years.

General Manager Frank Selke of the Montreal Royals threw a little fuel on the fire with his comment:" Olympic hockey is now a fiasco as a result of phoney

amateurism which has spotlighted the harmful hypocrisy which has made it impossible for Canada to send a top-notch, simon-pure hockey team to the Olympics.

It is certain that many that will be taking the Olympic oath are stretching the truth, that players had received money for sport services, yet compete in Olympic games.

Every player of the Allen Cup Champions is on our payroll. What's more, we believe they deserve to be".

To have gotten a civilian team capable of meeting the Olympic standards Canada would probably have had to dig into the junior or midget ranks. Frankly, strict amateurism went out away back. For 8 years there has been no CAHA rule against amateurs taking money, and acceptance of gratuities in any form meant automatic Olympic disqualification. The feeling was that a first class team should go, or none at all. The thoughts were that the assembling of such a team was no overnight job, nor was it a job that could be crammed into a few days or even weeks. Faced with no team meeting the qualifying standards answering the call; and what seemed as few options to put together a good enough team to compete, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) announced it would not be putting forth a team for competition at the 1948 St. Moritz Olympics!

Hockey is as much a symbol of Canada as the maple leaf. Canadians take great pride in our ability to be the best in the rink. The Prime Minister's office was flooded with letters from outraged Canadians at the thought of not having a representative hockey team. The PMO initially said there was nothing that could be done.

It was at this time that Squadron Leader (Doctor) Alexander Gardner "Sandy" Watson, a senior medical officer at RCAF Headquarters in Ottawa, saw an Ottawa Citizen newspaper headline saying there may be no team.

|

| ||

|

|

Sandy would have nothing of it. This was unacceptable

to hockey enthusiast (some would say fanatic) Watson.

(Watson had some prior hockey credentials – Watson had managed a series of exhibition hockey games in England in the months following the

defeat of Germany, pitting the air force against the army. The games featured such National Hockey League players as left–winger Roy

Conacher, a sniper for Royal Canadian Air Force teams during the war. He was also in charge of the hockey squad which represented Overseas

Headquarters in games which were played in Switzerland in February, 1946, and also at Wembley Stadium, London in April 1946 beating probably

the strongest European team – the Czechoslovakians.)

Working out of RCAF Headquarters in Ottawa, Watson immediately went to see his air force superiors. In those days the RCAF could solve anything, and often did!

Watson convinced the "brass" that the Royal Canadian Air Force could take the bold initiative and field

a good team, just by selecting the best players from RCAF Stations all over the country.

(The RCAF's postwar enrolment of 16,000 promised a wealth of hidden hockey talent.)

Team membership would be based on an individual's current hockey stats. And this type of team formation could all be done on a shoestring budget.

That sounded good to Chief of Air Staff, Air Marshall Wilf Curtis, who gave the nod.

Watson then, with RCAF brass authorization, worked hard to get approval from the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association and Canadian Olympic Committee and began promoting the RCAF as a resource for skilled players from which an "ace squad" could be put together.

Watson was a very skilled promoter.

The CAHA and Olympic Committee agreed, as did Defense Minister Brooke Claxton, just forty–eight hours before the International Ice Hockey

Federation's Olympic entry deadline.

Defense Minister Claxton, also an avid hockey fan, was a constant advocate of "tri–service

activities". However, on 16 October 1947, after receiving many pointed requests to make the team an "all military show",

Claxton said;

"The original invitation was to the RCAF and that's the way it will stand."

Refs: 8.1 & 8.2

The decision delighted the air force. But it infuriated the army – who would later exact a form of revenge.

The team would be strictly airmen and would be called the RCAF Flyers.

One air force official involved with " Operation Olympic" boastfully stated:

"If we can't pick 15 good amateur hockey players out of 15,000 RCAF airmen scattered across the country, then nobody can! "

The RCAF Flyers would be entrusted with bringing the gold medal back to Canada and representing its 12.5 million citizens.

The selection of the RCAF Flyers to represent Canada in Olympic hockey eased the painful "no hockey team" nightmare which had troubled both the CAHA and the Canadian Olympic Committee for months. Everyone agreed that the airmen should have no trouble recruiting a strictly amateur team.

Squadron Leader Watson expressed delight that it had finally been arranged that Canada, the home of hockey, would compete for the Olympic title.

Watson commented in October 1947:

"Naturally we want to make a worthy showing for Canada, and while our course for the moment is somewhat uncertain, we have every

intention of presenting the best possible lineup".

One Air Force official at the time said:

"We have every intention of giving this an all–out try. We feel we can do a good job for Canada at the Olympic Games and we

are going to bend every effort in that direction".

|

In early October, messages were sent to all Sports Officers on Air Force stations across the country with a view to informing the hockey minded that everyone qualified – with Junior A or higher experience – should be ready for a try–out.

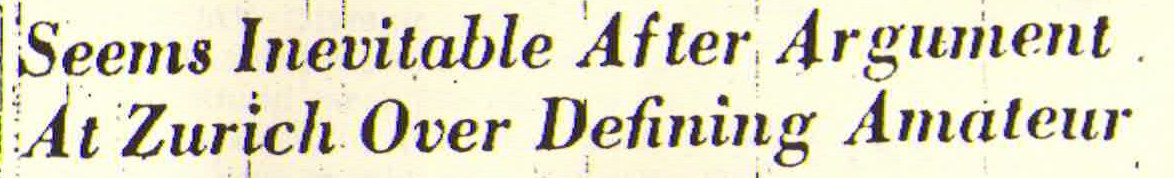

Unfortunately, the best RCAF line of all–time was not eligible – Milt Schmidt, Bobby Bauer and Woody Dumart, who played for the RCAF during the war, but were also unfortunately NHL veterans.

Historical Note: It may initially appear unusual that a Canadian military team was seriously considered as a candidate to represent Canada at the winter Olympics.

However the history of the game of hockey is intertwined with Canadian military history.

Some of the first images of the winter sport that became a Canadian icon and some might venture an obsession; depict players in military uniforms cavorting on the ice ponds of eastern Canada.

The Canadian national character has been greatly influenced by the sport and so too has the character of the Canadian military. The tradition of sporting competition has long been associated with military forces. Canadian regimental, squadron, base and ship's hockey teams have competed with each other over the years and represented Canada in international competitions. Further, during the war, emphasis was placed on traditional military fitness and sports. Recreation programs were nonexistent. In order to cope with the social and welfare needs of the rapidly expanding Air Force, private agencies such as the Auxiliary Services were called upon to assist with the leadership and financing required to provide suitable recreational and entertainment programs. During this period, the emphasis was on participation in sports and games, with station teams competing mostly, and often quite successfully, in civilian leagues.

A common job for NHL draftees was as a physical-education instructor at a training base, and they were also often pressed into service on armed forces hockey teams with the intent of boosting civilian and enlisted morale. The most famous team was the Royal Canadian Air Force Flyers, a senior team stacked with enlisted NHLers, including the entire Kraut Line from the Boston Bruins - Woody Dumart, Bobby Bauer and Milt Schmidt.

|

|

|

Wartime hockey followed the troops to Europe. And 419 Squadron was no exception. For the men of 419 Squadron the ice rink at Durham near Middleton St. George and other surrounding Canadian bases

was a chance to bring a bit of home to their war time surroundings.

The ice rink at Durham had local players taking part in hockey games since 1942. The arrival of the Canadians and the teams each squadron put together gave the crowds at these games a short respite from the war going

on around them.

NHL players such as the aforementioned Boston Bruins star line up the known as the "Kruat Line" comprised of Milt Schmidt, Woody Dumart and Bobby Bauer were now playing on teams at Durham.

Schmidt and Bauer were stationed at Middleton St. George, Dumart was stationed at Linton. The three men were all from the Kitchener-Waterloo area of Ontario and were the first of many NHLers to join the RCAF.

The rink in Durham would provide all the hockey players a unique and sometimes humorous twist to the game. The rink's supporting posts for the roof were located right down the center of the ice while two other

posts at each end supported the roof near the place where the defensemen positions normally were.

The

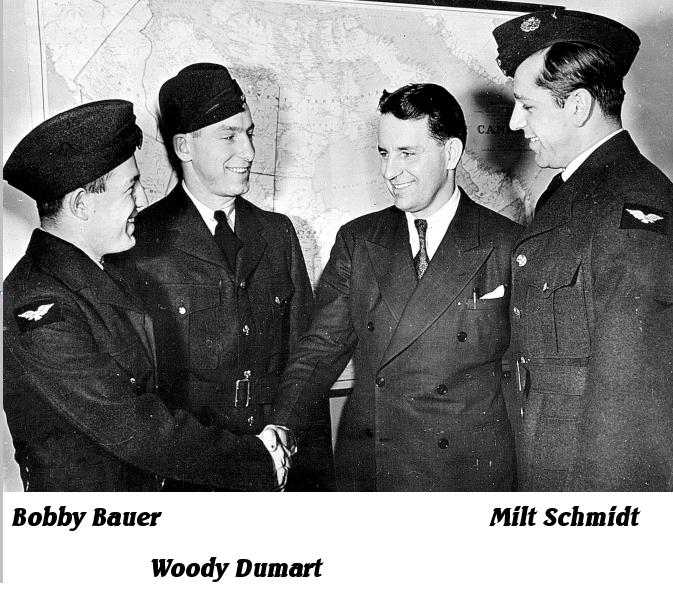

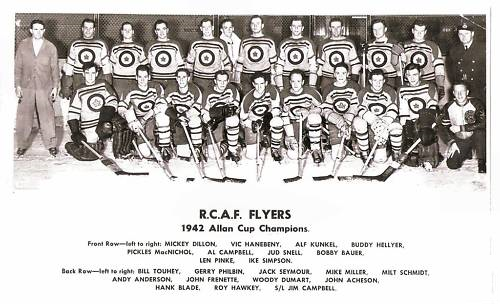

RCAF Flyers had a senior amateur Canadian ice hockey team, based out of Ottawa who won the Allan Cup Canadian championship in 1942 !

A brief retrospective Ottawa Journal article of the 1942 team by goalie Len Pinke can be found by double clicking the following

LINK

See also Nitzy's Hockey Den site

LINK for some photos and team biographies from the City of Toronto Archives.

|

|

Not to be outdone, New York Rangers coach Frank Concher was instrumental in forming the Ottawa Commandos, an all-star army team created expressly for voluntees from professional hockey.

After the Commandos won the 1943 Allan Cup, teams from Canadian military camps, chock full of NHLers, accounted for most (and in some cases all) of the slots in provincial senior leagues. Bases were actively recruiting

major-league talent to serve as coaches and players, and there were justifiable fears that what was supposed to be a recreational pursuit for men undergoing basic training was becoming a shadow league for the NHL,

keeping its players out of active combat while serving as a cash cow for the owners of arenas that hosted the games. Conn Smythe's Maple Leaf Gardens, for example, held the right to host all senior

games held in Toronto, including those of the Toronto Army Daggers.

Also in 1943, the

Toronto RCAF Flyers won the OHA Senior AAA Championship beating Toronto Navy 3-1. The team

then lost the semi final in the 1942-43 Eastern Canada Allan Cup Playoffs.

The Toronto RCAF Flyers started the 1943-44 OHA Senior Season but were forced to withdraw when the RCAF ordered its teams to pull out of civilian leagues.

In the spring of 1947 the Ottawa based RCAF team had beaten the Army team at the Ottawa Auditorium for the Inter–Service Trophy showcasing the caliber of players potentially available for the Olympic squad.

|

During the Second World War, the RCAF Flyers "Hurricans" Football Team won the 1942 Grey Cup.

|

Also during this time the RCAF had many Military Service Clubs who were active in FOOTBALL.

Camp Borden RCAF Hurricanes (1944) |

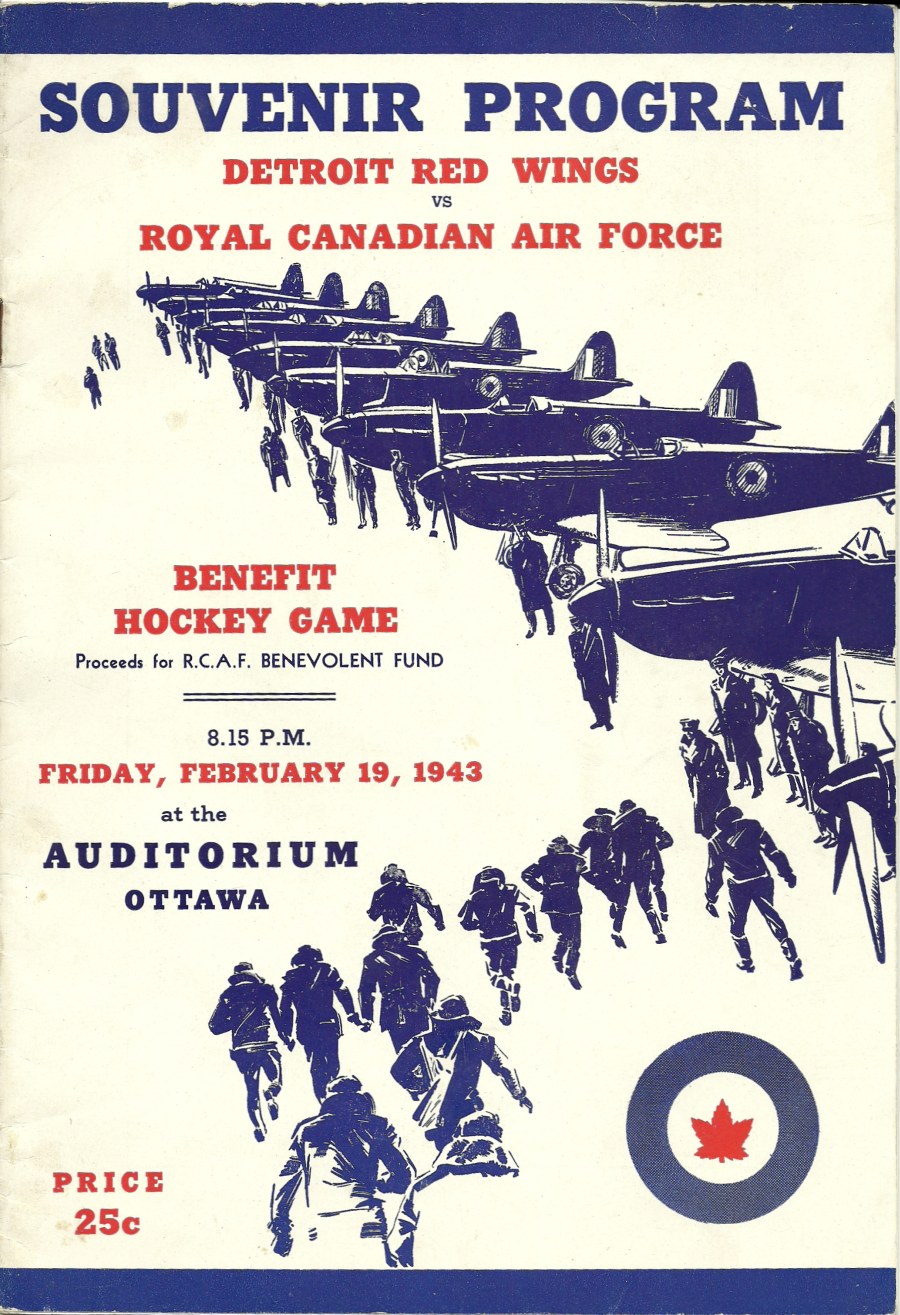

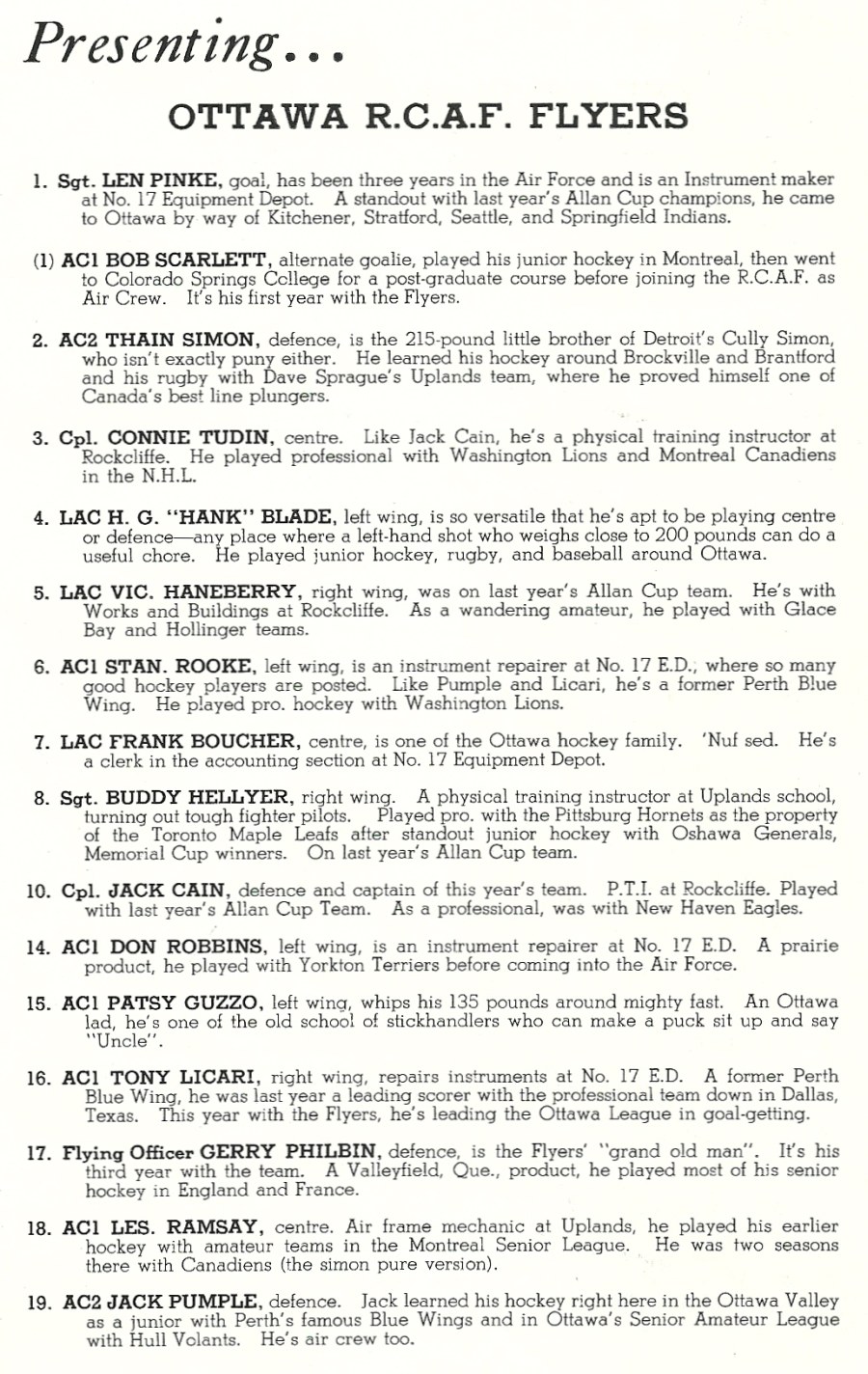

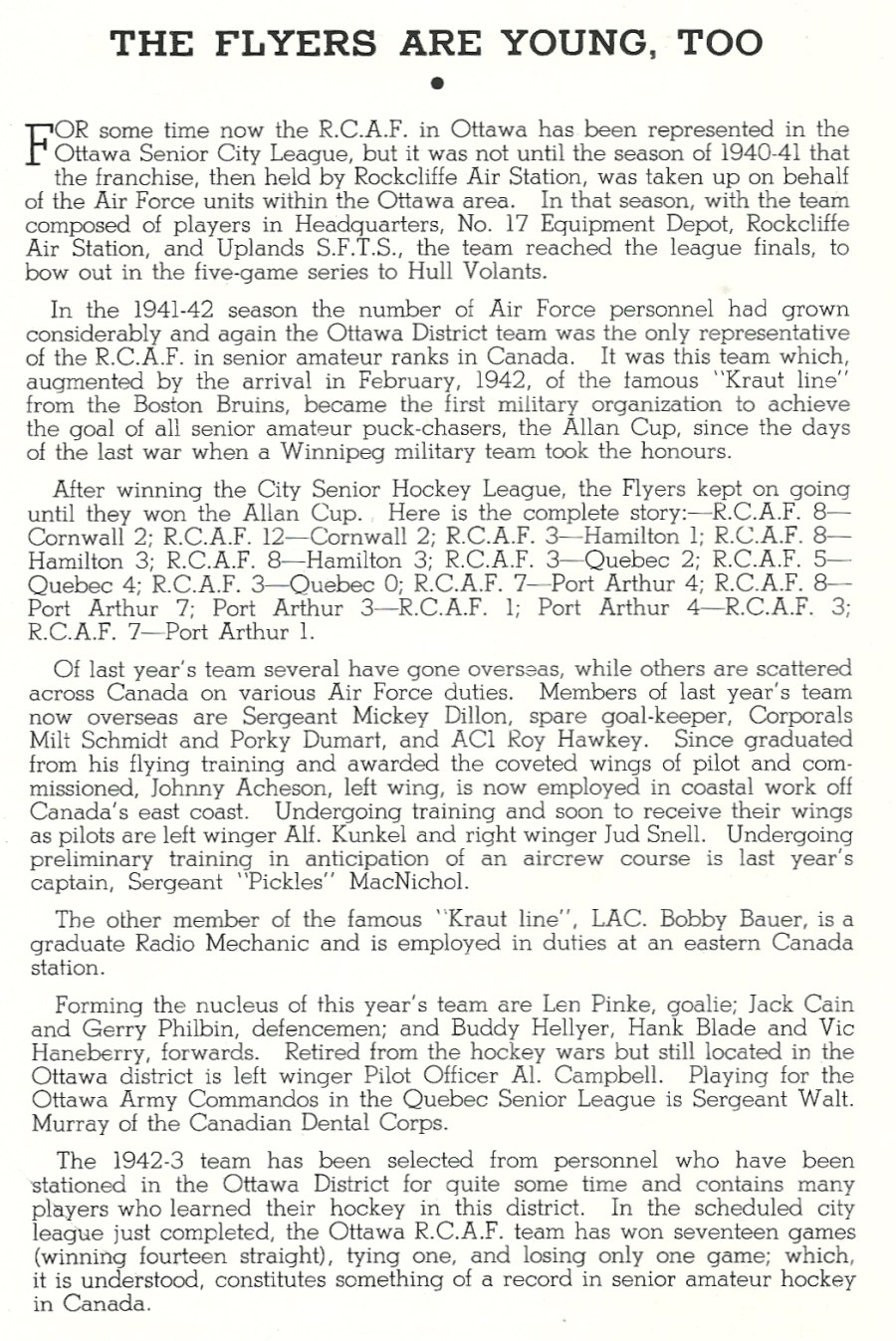

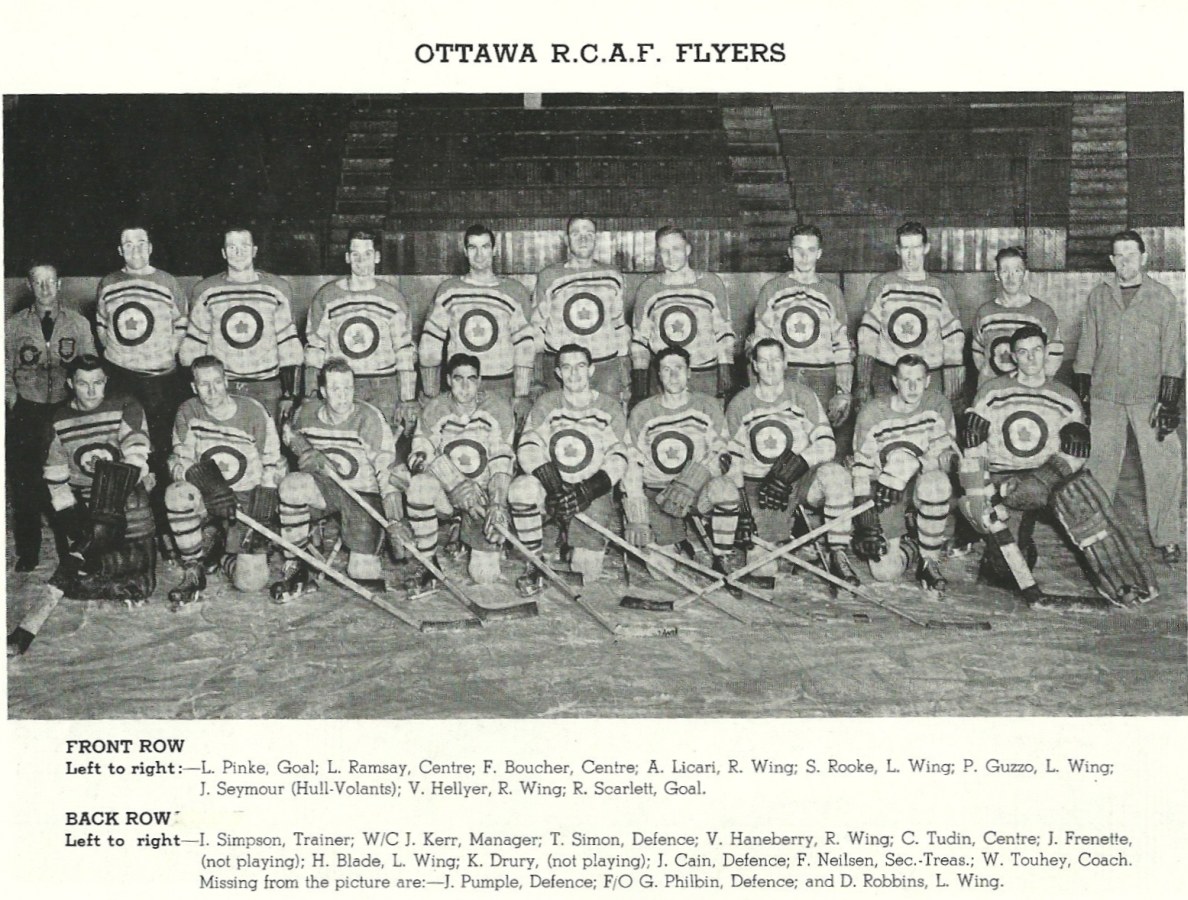

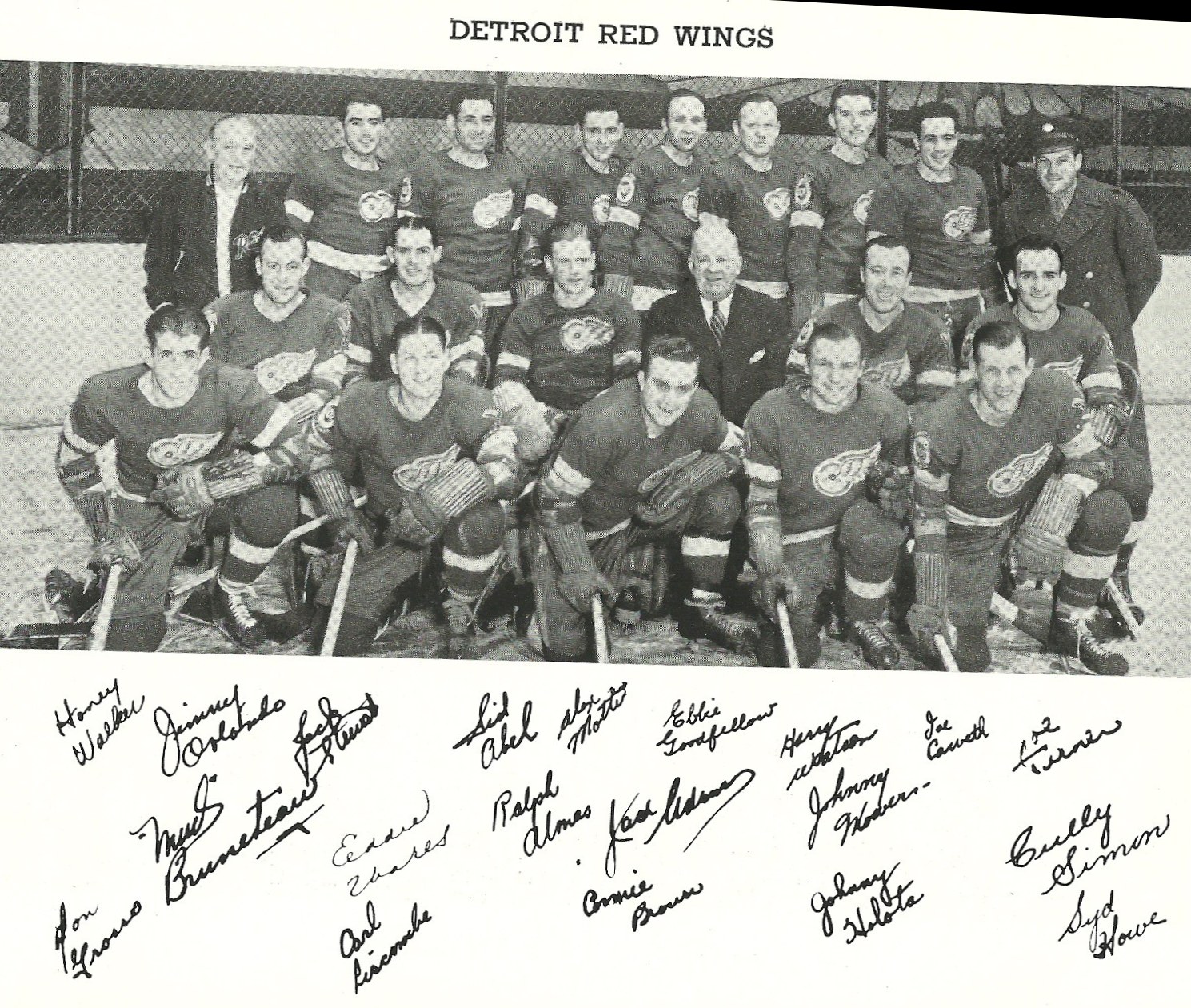

The RCAF maintained a "Flyer" team in Ottawa of some considerable skill through the 1940s. The 1943 Program for an exhibition game against the Detroit Red Wings - some pages of which are illustrated below (provided by the Estate of Pat Guzzo via his daughter Mary Rose), shows the makeup of the 1942-1943 RCAF Flyer team, including future 1948 RCAF Flyers: Patsy Guzzo, and Frank Boucher!

1942 / 1943 Ottawa R.C.A.F. Flyers (Hockey)

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| PREVIOUS PAGE | GO TO TOP OF PAGE FOR INTER- and INTRA- CHAPTER NAVIGATION MENUS |

NEXT PAGE |

The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks M.C. C.D.