The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks M.C. C.D.

A Canadian Hero

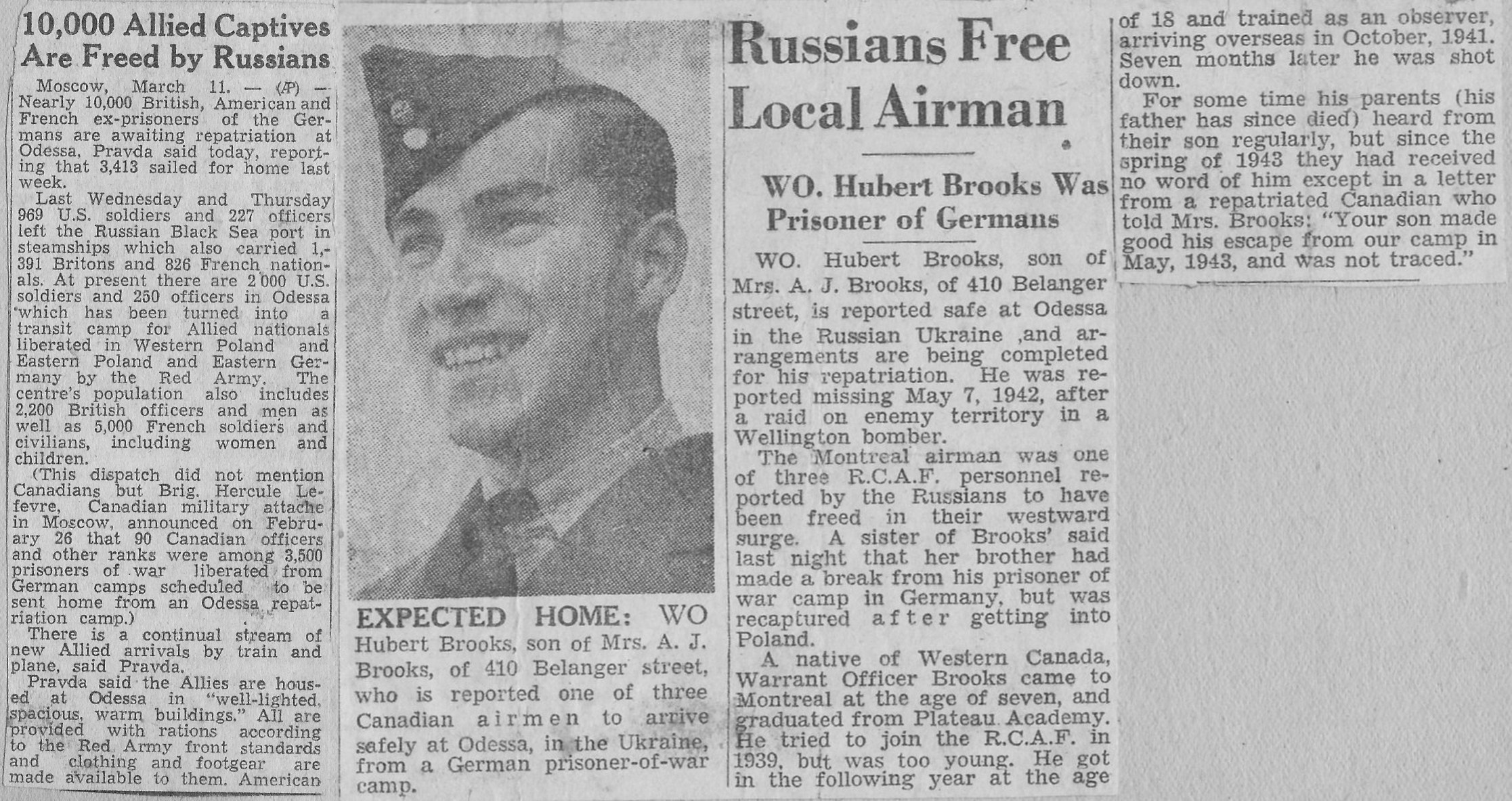

|

|

|

| |

|

The end was clearly in sight.

That Winter of 1944/1945, in the villages in which we had operated, we ate cakes and drank "monopolka", the potato gin of the region.

We had previously started to round up the girls who had gone out with Germans and shaved their heads.

That too was a sign the end was near.

We knew the Russians were advancing toward our positions.

At 2:15 in the morning of January 12, 1945 (see partisan communications message link) the Russians started their offensive and the front started its slow but steady movement forward. The Russians had waited for the rivers to freeze over before they started their movement west. The Russians were of the opinion that they would have the upper hand in the cold of winter.

John and I were on our way to Major Borowy’s headquarters to fetch money for the boys when I first saw the Russians. Their motorized columns were screaming down the highway.

Other British National Archives documents such as contained in file HS4_145 Ref 3.42 indicate that in the late September 1944 to early 1945 time frame there was some distrust that exsisted between the British Chiefs-of-staf, SOE and Polish Colonel Jazwinski with the the London based Polish Government in exile, and in particular General Sosnkowski. It is not clear if the infighting and the view of the limitations of aircraft flown out of Italy and the encouragement of false hopes played into the delay and/or planning of the Jodłownik rescue mission.

Despite General Sosnkowski's order that "local Commanders were to declare themselves to the advancing Soviet Armies and state that they were members of the Home Army" Ref 3.42 , the Polish partisans had been very blunt with the evaders telling them that once the Russians started to advance, they, the partisans, would dissolve into the woodwork. They further cautioned that if the evaders showed any recognition of their partisan protectors, they would have effectively signed the partisans death warrant as the Russians viewed the partisans as "bandits". Bandits were immediately shot. That was the degree of fear that the partisans had for the Russian liberators.

Late that night, we slipped back through the Russian front line to our hideout only to find the U.S. boys already gone with only F/Lieut. Schoffer remaining!

F/Lieut. Schöffer told us, and later would state in his MI9 Main Report brief

Refs: 1.19:

" I told (the Americans) to wait a few days until the first line troops

had passed, but they would not listen and departed on their own.

Schöffer had then waited for this first wave of Russian soldiers to pass whereupon John and I had returned to the safe house in Szyk.

A few days later, the troops of the Soviet Army launched the "liberation" of Limanowa. (The rivers had by now all frozen allowing the Russians to advance and move west quickly closing the roughly 150 mile distance to Ochotnica.)

On 19th January 1945, Polish AK Army Commander General Leopolda Okulickiego had given formal orders to dissolve the Armii Krajowej. Accordingly, Major Borowy was ordered to disband the brigade and disperse the men to their own villages.

John, F/L Władysław Schöffer and I waited until the second line of Russians went through and after several farewell "parties" with Father Hubert and others in the area departed for Warsaw, in the latter part of January 1945.

I'd heard through my partisan contacts that the NKVD was looking for two

British soldiers who'd fought with the Armia Krajowa!! We were wearing khaki uniforms now that had been sent to the partisans on the

various para–drops from Italy and our cover story was that we'd just escaped from a POW camp.

John and I intended to intentionally kept a very low and very passive profile from the moment we encountered the Russian line.

Schoffer threw away his Polish Air Force identity card and used an old RCAF station pass to convince the Russians he was a Canadian, since we were certain that he would be shot immediately by the Russians if they thought he was a Pole.

A Russian patrol soon picked us up.

Then began our travels – and the long route home.

We were received by the Russians without any enthusiasm and made to force march with them toward the front line on the Oder River.

A week later, we were once again compelled to walk from Bielsko to Nowy Sącz, Poland, a distance of approximately 120 miles. At Nowy Sącz we were locked up and interrogated.

Eventually, our American friends rejoined us in Nowy Sącz This was roughly early February 1945.

After the end-of-the-barrel encounter with the Ukranian soldier at their farm house in Szyk, the allied evaders at Szyk decided to try to contact the Russians directly themselves. (Schöffer was the sole voice urging caution against immediate action.)

In the morning of January 21 Spencer Felt sent the two navigators, Hansler (who spoke some German) and Tad Dejewski (of Polish descent and fluent in Polish), out to search for the Russian headquarters.(They probably broke all rules of escape dressing in civilian clothes - for which they could get shot!) The objective was to contact some Russians "administrators" in a local village that were staying put; and not to get hooked up with the troops moving west. When they were walking along a country road, two Russian soldiers came over a rise and after some routine questions let them go at first, but then stopped them by shooting over their heads. They took them into custody at the end of clearly trigger-finger-ready rifles and marched them to a school house near Tymbark where they were brought before a Russian captain.

As a rule, Russian front line troops were certain to be drunk. This Russian captain was very drunk. His first and only impression was that Tad was a German. He proceeded to pour

have a glass of "friendship vodka, and said;

"Drink it, because after you have drank it, I'm going to take you out behind the barn and shoot you."

Tad proceeded to drink the vodka as slow as he could. Finally the captain took him out behind the barn,

and just as he was about to shoot Tad, a Russian colonel came into view and stopped the shooting. It was that close. Hansler and Dejewski would later say that this first encounter with the Russian captain

was the scariest portion of their whole ordeal - they thought they would be summarily executed without a thought.

The Russian colonel had them driven to Tymbark where they were interrogated. The colonel along with Dejewski went off in the colonel's staff car to pick up both American crews and the other Allied evaders. Hansler was kept behind as a hostage.

After reacing the farm house where the rest of the Americans were staying, the colonel dined with them and eventually let his guide march them to Tymbark.

From then until February 1 the party of allied evaders moved on foot and by truck through the whole area in search of military headquarter authorities who could evacuate them. However the headquarters, like the frontline, was moving fast and constantly changing. The travel saga unfolded as follows:

On February 1, General Alexander Novikov ordered that information be taken from the men and radioed Moscow for further action.

As mentioned early, we eventually met up again with our American evader friends in Nowy Sącz early February 1945 time frame.

We were billeted for 2 to 3 weeks in a school house little apartment house that was in reasonable condition.

However things got tighter and tighter for us as "guests" of the Russians in Nowy Sącz. Our accommodation was an apartment with the bathroom facility across the street, a slit trench behind some bushes. Once a week we could have a bath of sorts down the street. Our sleeping quarters were on the second floor and the dining room was on the first. The Russians had a guard posted around the clock in the courtyard. The courtyard was in the back of the house and the dining room was facing the front. We could jump out the first floor window and go into town if we were cautious. During this time we were all treated more or less as prisoners and continued to receive very bad food, although the Russians themselves fared very well. We had one meal a day and everyday we had barley.

Some occurences remebered from our stay in Nowy Sącz include:

Editor's Note:

Richard Hansler's Eventual Evacuation Story:

Hansler remainded in various hospitals under Russian care. On March 14 he was taken back to headquarters a Nowy- Sacz. where he stayed for two days.

He was taken the alternatively by truck and tain, with good care en route, and arrived in Odessa on March 22. He stayed in a temporary camp until March 27 when he received the order to sign up for a sea trip.

He sailed to Odessa on the S.S. Circassia and arrived in Naples on April 2, 1945. Hansler was taken to the replacement center where he gave his statement.

He highlighted the pre-flight briefing advice to not attempt a landing behind the Russian lines had been wrong and needed to be reconsidered.

He also recommended bombardier 2nd Lt. Kroschewsky for a Silver Star for carrying on after having been wounded and shooting down a Me-109.

One day the Russians brought in Sgt. John W. Dyer (36194424) from Saginaw, Michigan a ball turret gunner of a B24 Liberator crew of 464 Bomber Group into our apartment.

Dyer had spent the war evading in Slovakia. Dejewski and Felt interrogated him to ensure that he was not a plant -- as the Russians

had tried with other so called evaders. Dyer was quickly OK'd.

Another day they brought in a pilot who said his name was "Davy Jones" and that he'd bailed out over "Breslau Germany" - a city 300km away.

Felt asked him where his home was in the States. He answered "Shamokin, Pennsylvania." Neither Felt nor Dejewski believed a word he was saying so either this guy had deep secrets to protect or this was a German

plant - although everyone found it difficult to believe that even the Germans would make up a story so implausible. Everyone just stayed away from "Jones".

At this time the group in the apartment consisted of of 21 men:

| Nationality | Serial No. | NAME | Military Affiliation | |

| 1 | CANADA | (R56265) (J94368) | Sgt. Hubert Brooks | Navigator Wellington X3467 - R.C.A.F 419 Moose Squadron |

| 2 | SCOTLAND | (2873963) | Sgt. John Duncan | Infantry Sargeant 51st Division Gordon Highlanders |

| 3 | POLAND (Resides U.K.) | (P1961) | F/Lieut. Władysław Schöffer Going by name "Stanley Staf" | Captain 301 Polish Bomber Squadron (1586 special task wing) associated with Mediterranean Allied Air Forces (MAAF) |

| 4 | SOUTH AFRICA | (11721) | Rfn. B. J. Curtis | Not Known |

| 5 | BELGIUM | (30856) | Sgt. F. Slosse | Not Known |

| 6 | U.S.A. | (0.722848) | 2nd Lt. Richard L. Hansler | B17 Navigator U.S.A.F. 817th Bomber Squadron of 483rd Bomber Group part of 15th Air Force Command |

| 7 | U.S.A. | (0.1795526) | 2nd Lt. Gus John Kroschewsky | B17 Bombardier U.S.A.F. 817th Bomber Squadron of 483rd Bomber Group part of 15th Air Force Command |

| 8 | U.S.A. | (36826944) | S/Sgt. Gordon W. Sternbeck | B17 Arm. Gunner U.S.A.F. 817th Bomber Squadron of 483rd Bomber Group part of 15th Air Force Command |

| 9 | U.S.A. | (36482329) | Sgt. Aloys C. Suhling | B17 Asst. Rad. Opr. U.S.A.F. 817th Bomber Squadron of 483rd Bomber Group part of 15th Air Force Command |

| 10 | U.S.A. | (36377873) | S/Sgt. Harold E. Beam | B17 Asst. Eng. U.S.A.F. 817th Bomber Squadron of 483rd Bomber Group part of 15th Air Force Command |

| 11 | U.S.A. | (0.2059017) | 2nd Lt.Spencer Felt Jr. | B24 Second Pilot U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 12 | U.S.A. | (0.2064229) | 2nd Lt.Thaddeus (Tad) Dejewski | B24 Navigator U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 13 | U.S.A. | (T.122067) | F/O Robert Nelson | B24 Bombardier U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 14 | U.S.A. | (39568564) | Cpl. Edward Sich | B24 Flight Engineer U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 15 | U.S.A. | (14185196) | Cpl. Walter Venable | B24 Wireless Operator U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 16 | U.S.A. | (12238645) | Pfc. Jack Blehar | B24 Lower Tower Ball-Turret Gunner U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 17 | U.S.A. | (19124917) | Cpl. Clarence Dallas | B24 Front 'Nose' Gunner U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 18 | U.S.A. | (12228486) | Cpl. William McCuttie Jr. | B24 Tail Gunner U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 19 | U.S.A. | (11098611) | Cpl. Bernard Racine | B24 Side (top-turret) Gunner U.S.A.F. 757 Squadron, 459 Bombardment Group of 304 Wing of 15th Air Command |

| 20 | U.S.A. | (36194424) | Sgt. John W. Dyer | B24 Ball turret gunner of a B24 Liberator crew of 464 Bomber Group |

| 21 | U.S.A. | (???) | "Davy Jones" | Pilot with ???? |

The Russians told us that a General Novikoff wanted to talk to us in Presov, Czecho-Slovakia. They piled us all into a truck and headed south through Krynica, on the Polish-Slovak border, infiltrated some German pockets and into Sabinov, Czecho-Slovakia, and on to Presov only to find out that the general was waiting for us in Nowy Sącz where we just came from. After spending one night in Presov the following morning we got back into the truck and headed north back to Nowy Sacz. General Novikoff, through a Cossack Major interpreter, asked the men if they needed anything. McCuttie mentioned he would like to go to church as it happened to be Ash Wednesday. The General answered bruskly "in Russia.we don't believe in going to church". And that was that.

I wanted to let London know exactly where we were and who was with me. Fortunately, Nowy Sącz was in our operating area. One night I slipped out of the first floor window of the house we were confined to and headed for the home of an A.K. partisan. I had him deliver a note to Borowy who radioed our message to Britain announcing that I, along with 18 Americans, three British and one Belgian, were being sent via Lwów (Polish) (Lviv in Ukrainian) and Kiev to Odessa.

I do not know whether my message to London was received and, if so, caused the immediate actions which followed. However, shortly afterwards we were fitted out with Russian uniforms, fur hats, boots and riding breeches, but no socks! In place of socks they again gave each of us two squares of white cloth. We had to learn how to fold these to make foot coverings without pinching our toes.

On February 22, 1945 without warning, the entire party was given a bag of black bread, some preserved butter and sardines and they were told to get in a truck and told they were going to move. Some people in Nowy Sącz who heard that we were leaving came over with cigarettes and some foodstuffs to share with us. (We later heard that our Russian liberators had gotten word from Moscow or to send us east to a town called Lviv.)

The group of us went by truck to Lwów where we stayed a few days at one of the best hotels in town, the Hotel George.

Lwów (Lviv in Ukrainian) was a comparatively big city that was originally a Russian town, then a Polish town, and finally a part of Poland that Russia took over.

At the Hotel George in Lvóv:

On the final day of our stay in Lwów the Russians took us to a theater to watch an Anti–American play. The theater usher gave us center seats in the second and third row, the perfect seats. As fate would have it, I happened to get the center seat in the second row. In comes a high ranking Russian general demanding my seat. Not wanting to sit with a Russian General the men quietly whispered not to give it up. An argument ensued between myself and the General which got a little heated finalized by all us getting up and walking out. The management begged us to stay but we just left. Although both myself and Schöffer (who the Americans only knew as "Stanley Staf") were fluent in both Polish and Russian all of our conversations now were exclusively in English as John and I were listed as "bandits" by the communists.

The last day, before we left Lwów (Lviv in Ukrainian), we had breakfast in our private dining room and when we finished, the commissar brought in the check. The guests of the government were now to be paying customers! He handed American Tad Dejewski the check. Tad told the commissar that; "the bill shouldn't come to me rather it should go to Captain Staf (Schöffer) as he is the ranking officer of this group". The Russian accepted this logic while "Stanley Staf" scribbled his name, rank and serial number "1945" (sic). The bill was something like 645 rubles. On the exchange it was $5 dollars for each ruble. This came out to be about $153 per person. At that time, inflation was rampant and the communists must of figured "let's stick it to Americans". I’m sure that bill was never paid!

On the serious side, I later reported to M.I. 9 the following items arising from conversations with Poles whom I met in Lwów:

I considered that the position of the Poles after the entry of the Russians was far worse than before.

In my area, the Red Army completely devastated the countryside, looting absolutely everything movable from the houses, even including furniture. Members of the educated classes were being arrested and information as to their fate after arrest was not available.

At the time of my departure, the A.K. had gone back into hiding and were determined not to reveal themselves to the Russians.

The Soviet and Polish communists viewed most of the Polish underground, which was loyal to the Polish

government–in–exile, as a force that had to be removed before they could gain complete control over Poland.

(I later

learned that future General Secretary of PZPR, Władysław Gomułka, was quoted as saying: "Soldiers of AK

are a hostile element which must be removed without mercy." Another prominent Polish communist, Roman Zambrowski, said that

the AK had to be "exterminated.")

In fact members of the AK were being rounded up, shot or deported to the East.

On February 25 after breakfast, the Russians took us to the railroad station and put us on a train to Kiev and then on to Odessa.

We were marched to the train and boarded cattle box cars, 35 men in each small car and 65 in each large one. The Russians issued about 100 lbs of hard tack for each car.

(Hard tack is a simple type of cracker or biscuit, made from flour, water, and sometimes salt. Inexpensive and long-lasting, it was and is used for sustenance in the absence of perishable foods. The name derives from the British sailor slang for food, "tack". It is known pejoratively as "dog biscuits", "tooth dullers", "sheet iron" or "molar breakers".)

In addition the Russians apportioned enough tea for about 3 meals, some salt pork (fat) and some American porridge, but no utensils to cook it. This was supplemented by some bread and sausage. Each car contained a small stove but very little fuel. As we were unable to eat the hard tack (it wouldn’t break up when pounded with rocks) we burnt it and it made excellent fuel!

After a day and night ride in a third class coach, we arrived around midday in Kiev, a drab and desolate town. Here we did not see one building with a window intact. We went through a big part of the city to a military barracks where we had a shave and haircut.

As a comment, our train was often put into sidings while trainload after trainload of "loot" went past heading east. The trains seemed to contain factory machinery, furniture machinery, furniture, sewing machines in fact anything! In addition there were train cars with horses, and some packed with German male civilians (rumored to be any German between ages of 17 and 50). Quite the sight.

In the evening of the same day we left in a crowded train for Odessa. The men gave Spencer Felt a little birthday party on the train on February 27, 1945. The Russians joined in with signing and dancing down the aisles with Russian style dancing. Felt reported that this was one of the best birthdays ever!

This was a rare, almost unique case of Russian friendliness. Most POWs who had come into contact with the Russians looked on them as the crudest, drunken barbarians who devoured everything like locusts, who despised all other nationalities and who frankly didn't see how the plight of those countries over-run by the Russians could be worse than it was under German occupation. This was particularly the case with Poland. Wholescale looting and rape was the norm. The Polish countryside was being stripped of all food.

We arrived in Odessa early March 1945 where we were taken right away to be deloused, fed and finally quartered.

In Odessa, we all split up and were confined in repatriation camps according to nationality. The camp for Commonwealth soldiers that I was at was known as Camp 9 under the command of a Major Croft. I was there for approximately two weeks before shipping out to Port Said. Food and accommodation at Odessa were very bad. In this connection the News Chronicle headlines of 22nd March saying: "FIRST PRISONERS HOME FROM ODESSA SAY RUSSIAN FOOD MARVELOUS". This was doubtless said sarcastically.

As a direct result of my repatriation in Odessa, the following telegram was sent to my parents:

Although the authorities notified my parents on 5–March–1945, I was later to see

correspondence dated after this date that indicated that "..it is not definitely known whether W/O Brooks or the person

with whom he exchanged identity has arrived at Odessa….".

Perhaps the authorities were uncertain if this was the Kiwi Private Frederick Cole with whom I had exchanged identies with back in Stalag VIII B.

My parents just didn't know what to think.

After spending about seven days in Odessa the crew was told on March 6, 1945 to to sign up for a sea trip for Port Said, Egypt.

There were 3 ships designated to leave Odessa; the Moreton Bay, the Duchess of Bedford and the Highland Princess. I was to leave on the Moreton Bay.

The Russians had claimed they had no ships available to send Allied POW back across the Black Sea to Southern Europe. The Allied response to this explanation for lack of action was swift - they immediately dispatched a mini-fleet of Allied troop and hospital ships to Odessa. A memo sent from 30 Military Mission, Moscow to Middle East Headquarters in February 1945 advised that:

On 7th March ‘45 starting at 0900 hours we boarded an Australian troopship, the S.S. MORETON BAY, with about 1,700 all ranks (500 British Commonwealth and 1,200 Americans) for Port Said. Embarkation was completed by 1200 hours, taking longer than expected as the Russians insisted on checking off each man on their list.

|

Embarkation was then temporarily held up as the Russians suddenly produced 2 documents for the Allied authorities signature; the first specifying that a certain number of troops

had embarked and that there was no complaints against the Soviet Union, and the second declining to accept ten days provisions for all embarked. Once this blackmail was sorted out we embarked at 1300 hours.

Canadian Philip Anderson was appointed Messing Officer and was assisted by 4 NCOs –

one of which was Scotsman Sgt. W.S. McPhail who I became good friends with.

We sailed through the Bosporus, into the Sea of Marmura and through the Dardanelles, down through the Aegean and Mediterranean Sea and into Port Said, Egypt on March 12.

We anchored at the north end of the Suez Canal. We were anchored just off shore and opposite The Great Mosque.

We had reached Port Said on 12th March 1945, where we remained aboard ship until 15th March when the R.A.F. personnel were taken off and sent to Cairo.

We remained in Cairo until 18th March and were housed on the outskirts of Cairo at General Base Depot at RAF Almaza, No 22 P.T.C. (Primary Training Centre) under canvas.

Once in Cairo, I was almost immediately extracted and flown on to London.

| PREVIOUS PAGE | GO TO TOP OF PAGE FOR INTER- and INTRA- CHAPTER NAVIGATION MENUS |

NEXT PAGE |

The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks M.C. C.D.